Grappling with Cold War History: Korea’s Embattled Truth and Reconciliation Commission [With interactive video]

Gavan McCormack and Kim Dong-Choon

Introduction (by Gavan McCormack)

For the countries of Northeast Asia to construct a future Northeast Asian community, or commonwealth, along something like European lines, a shared vision of the future is necessary, and for that they must first arrive at a shared understanding of the past. The turbulent 20th century of colonialism, war, and liberation struggle looms as a large obstacle. Most attention focuses on Japan (Has it admitted, apologized, compensated for its crimes? Has it been sincere?), or on China (Has it faced the catastrophes of its revolution, including the Great Leap and the Cultural Revolution? Has it acknowledged or apologized for them?). As the “Great Powers” of East Asia, however, both Japan and China strive to construct a pure and proud history and identity, and to divert attention from the dark episodes of their past.

Korea is often overlooked. Yet its approach reflects its experience, unique in Asia, as a civil society that has grown out of decades of struggle for democracy and against fierce repression under US-supported military regimes, culminating in the uprising of 1987 and the steady advance of civil democracy in the two decades since then. The Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established to explore precisely the sort of skeletons in the national cupboard that many in Japan (most recently General Tamogami, the sacked Chief of Staff of the Japanese Air Self-Defence Forces) refuse to acknowledge, documenting the claims of the countless victims of former regimes and actively exposing its shameful past. It is the sole example in Asia of systematic attempt to explore the wrongdoing of its own governments, seeking closure and healing. Its mission, as author Kim Dong-choon described it in a recent book, is to “touch the untouchable.” Other Commissions existed, and continue to exist in Korea, to investigate the Kwangju Democratization Movement of 1980 (set up in 1990), or the Jeju Massacre of 1948 (set up 2000) or collaborations with Japanese imperialism (set up 2004), or suspicious deaths in the military (set up 2006) etc, but the TRCK has been unique in its broad scope, large staff, and its character under special legislation independent of any section of government, even the (Presidential) Blue House. It is modelled loosely on the South African experiment set up in 1995, after Nelson Mandela came to power. Similar Commissions have also been set up in a dozen or so other countries, mostly in Africa and Central and South America, including Argentina, Chile, El Salvador, Guatemala, Liberia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and East Timor, but none elsewhere in Asia. The TRCK’s work – some of its findings highly sensational and shocking – has been reported in the international media – notably Associated Press and the BBC - but its implications for historiography of the 20th century and as a model of possible regional relevance, remain to be digested.[1]

In Korea itself, the political support for the truth and reconciliation process weakened with the transition from ten years of progressive government to the conservative administration of Lee Myung-bak at the beginning of 2008. The Commission is now, in Kim Dong-choon’s word, “embattled.”

Focussing especially on the Korean War, the path to it and the long Cold War that followed and entrenched its legacy, Kim Dong-choon here concentrates on South Korean responsibility, as one would expect, and makes only passing mention of the United States and none at all of the United Nations or other countries that served under US command but the UN flag, in Korea between 1950 and 1953. Clearly, the Commission’s finding that upwards of 100,000 people were slaughtered by South Korean forces during that conflict affects the way that the Korean War has to be characterized, and whether their forces were directly involved or not, all countries fighting with South Korea, and the UN itself, bear some responsibility for the atrocities and subsequent cover-up.

The scope of the national project for truth and reconciliation does not extend beyond Korea's borders, but Kim Dong-choon here underlines the failures of Japan, China and the United States to come to terms with their own war atrocities. Korea is the only former member of the US-led coalition that fought in Vietnam to have made steps, however tentative, to apologize for the "pain" (Kim Dae Jung's word in 2001), caused to the Vietnamese people. No such US reflection has begun.. It may be far from perfect, but Korea nevertheless constitutes a beacon of light in Asia calling on all countries to do what they must do if democracy is to advance: honestly face their past. If Kim Dong-Choon is right that the Lee Myung-bak government is intent now on closing it down, that is surely to be deeply regretted.(GMcC)

South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (hereafter: Commission), set up in 2005 by the special law called the ‘Framework Act’. It has been a major fruit of decades of Korea’s democratization movement and its liberal government.

| Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Republic of Korea, |

| Established under the ‘Framework Act on Clearing up Past Incidents for Truth and Reconciliation’, May 9, 2005 The Commission is made up of fifteen Commissioners (eight recommended by the National Assembly, four appointed by the President, and three nominated by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court), of whom four are standing commissioners (two recommended by the National Assembly and two nominated by the President). The Commission’s initial term is four years with a possible two year extension. Petitions on the following matters are investigated: 1. Anti-Japanese movements during Japanese rule and in the years following Korea’s liberation; 2. Efforts by overseas Koreans to uphold Korea's sovereignty and enhance Korea's national prestige from the Japanese occupation to the enforcement date of this Act; 3. Massacres from August 15, 1945 to the Korean War; 4. Incidents of death, injury or disappearance, and other major acts of human rights violations, including politically fabricated trials, committed through illegal or seriously unjust exercise of state power, such as the violation of the constitutional order from August 15, 1945 to the end of the authoritarian regimes; 5. Terrorist acts, human rights violations, violence, massacres and suspicious deaths by parties that denied the legitimacy or were hostile towards the Republic of Korea from August 15, 1945 to the end of the authoritarian regimes; 6. Incidents that are historically important and incidents that the Commission deems necessary. The Commission has a staff of 239, including eighty-four seconded from central and local governments. Its budget in 2008 was approximately 19.7 billion Korean won (just over $14 million), roughly half of which goes on personnel and half on operating expenses. |

TRCK Inauguration Ceremony and 1st plenary session, December 22, 2005

In May 2005, confronted with fierce opposition from the GNP, the Uri Party (the majority party at that time, now the minority Democratic Party) barely gained approval for the passing the bill to establish the Commission, with a restricted mandate. Thus, when the Commission launched its mission to investigate South Korea’s troubled past, including serious human rights violations under the anticommunist cold-war regime and mass killings during the Korean War, it did so with limited authority. Even during the two years in which it functioned under the Roh administration, the Commission was accepted only as an awkward or inconvenient organization by entities like the Korea Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA), Bureau of Police, and the Ministry of Defence. Yet their cooperation was essential for the Commission to obtain documents associated with past wrongdoings. Struggling with their unwillingness to cooperate, the Commission, whose initial mandate from the more liberal Roh administration was for four years, faces now a diminishing prospect of getting a two year extension.

Since 2008, however, with the election of the conservative Lee Myung-bak administration, discourse on justice and human rights, both of which had come to be highly valued over two decades, have given way to those of efficiency and competitiveness. With this shift, the Commission finds itself in increasingly troubled waters.

President Lee Myung-bak’s administration and the ruling Grand National Party (GNP) are intent on weakening or getting rid of so called “inconvenient” organizations that deal with past state terrorism and human rights abuses. Ever since its inauguration, the Lee Myung-bak administration has wanted to merge and abolish history truth commissions. Bills submitted to the National Assembly on November 20, 2008 by the Grand National Party’s Shin Ji-ho and thirteen other Assembly members, form a framework for combining the functions of the fourteen history truth commissions into one Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In view of the striking differences in the missions, mandates, and works of these organizations, the policy may be understood as a design to stop the commissions functioning.

The Commission remains situated at the core of the present administration’s attacks on organizations dealing with the pasts. Conservative GNP politicians, even though some of them cast votes for setting up the Commission as an independent organization, tend now to regard it as a legacy of the Roh Moo-hyun administration (2003-2007) which is not in accord with the philosophy of the current Lee administration (2008 - Present). The Commission is, however, legally protected and cannot be abolished without a revision of the law.

Of course the conservative Lee undoubtedly won the Presidency. And as the political landscape changed accordingly, conservative newspapers poured criticism on several organizations set up to address issues of past incidents, including the Commission, arguing that they had been a waste of taxpayers’ money. Extreme rightists openly demanded that the Lee administration abolish them. Eventually, conservative GNP lawmakers proposed the bill to consolidate several such commissions into one overarching entity, with greatly reduced resources including staff, and deliberations on that bill commenced in the National Assembly in December 2008.

The Commission, however, remains the first case among Northeast Asian countries of a government attempting to face its own past wrongdoings committed in the name of national security and state order. It is therefore a unique experiment. The US, which has been proud of its role as architect of modern East-Asian states by intervening in wars from World War II to the Korean War to the Vietnam War, has refused to admit its own misdeeds against the Japanese, Koreans and Vietnamese during those wars. East-Asia’s big two, Japan and China, have never officially acknowledged their dark past by investigation or by compensation. Japan’s constant denial of its past of inflicting sufferings on Koreans and Chinese is well-known to the people of the world. Its reluctance to admit its misdeeds against neighbouring Asian countries must be the main cause for the lack of positive peace in the region and the lack of progress on proposals for an East-Asian alliance, common market and common currency, along European lines. China may be on a par with Japan as well, as it denies state sanctioned slaughter of innocent people during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). At the same time, China has blamed Japan for not admitting to the Nanjing Massacre and to human experimentation with biological weapons. Both of these big two Northeast Asian nations have seen themselves as victims of Western powers such as the United States. South Korea, although it has long been victimized and remains a victim in the context of Northeast Asian international politics, has pursued a different path in terms of addressing the past.

At the three-party (Japan, China, South Korea) summit held in Fukuoka, Japan in December 2008, Japan’s Aso Taro and Korea’s Lee Myung-bak adopted a similar stance, agreeing to bury historical problems in order to concentrate on the economy. When we recall that the company run by Aso’s family during World War II had used Korean forced labour at its mines and that Aso had previously infuriated Koreans by defending wartime atrocities, Lee’s setting aside of history can be interpreted as a sort of priority to economic benefit over justice and national dignity.

Korean forced labourers of Aso Mining Co. in front of their dorm at the Atago Mines

His behaviour marked a striking discontinuity with past Korean leaders who had, at least rhetorically, asked Japan for apology. The Korean President’s change of position points to a reaffirmed right-wing solidarity among the U.S, Japan, and Korea. In part because U.S intervention in this region during the Korean War was welcomed as a liberation force and in part because of the inequality of state power among these countries, the victimization of Japanese people by US atomic bombs and of South Korean people by indiscriminate US bombing and strafing during the Korean War has never been raised as a political agenda. In neglecting history, these two neighbouring North-East Asian countries whose modern histories have been framed by the United States have continued to follow the guidance of the United States, a country that has never acknowledged its wrongdoings in interventions in wars in Asia and Latin America. In the name of building the Cold-War bloc against the Soviet-Union, the United States condoned and even supported Japanese war criminals and Korean pro-Japanese collaborators who thereafter played leading roles in rightist regimes in East-Asia. This tripartite Cold War alliance has stood firm for the last 60 years.

Starting from the late 1970s, Korea’s democratization movements significantly shook the Cold-War system. Korean activists saw that the Soviet-U.S conditioned national division had legitimized not only dictatorships and human right abuses but had also blocked any possibility of liquidating the remnants of Japanese colonialism. Political democratization was accompanied by nationalist discourse and by the overcoming of Cold-War legacies. It proceeded simultaneously with the old agenda of cleansing the legacy of Japanese colonialism, and it also brought back the issue of national reunification and of ‘recovering full national sovereignty’. This was because democratization in South Korea always tended to focus attention on the international politics that supported national division and on the U.S intervention in the Korean peninsula. The democratic transition in South Korea was also a chance to enhance Korean’s historical consciousness. Examination of the role of pro-Japanese collaborators under Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945) and of incidents such as that at No Gun Ri (July 1950) where U.S forces killed several hundred refugees during the Korean War, became part of the political agenda.

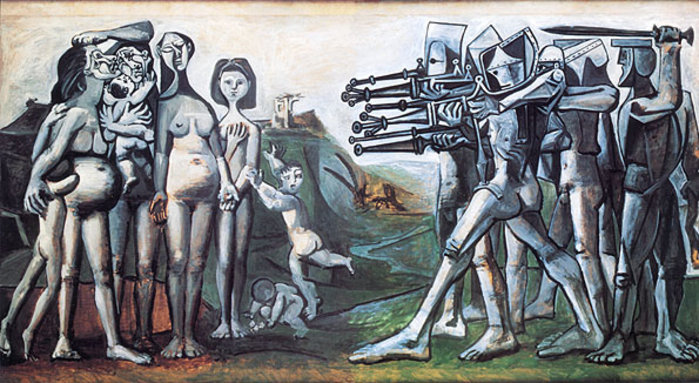

In July 1950, one month after the start of the Korean War, approximately 1,800 inmates of Daejon Prison were taken to nearby Golryeonggol and shot dead by the police and MPs

The setting up of several governmental organizations to address the issues of the past in Korea can be understood as the start of a serious examination of dark episodes under the cold-war tripartite alliance. The result is that many South Koreans learned that there had been many No Gun Ri and Gwangju (May 1980) massacre-like incidents before and during the Korean War. The April 3 Incident (1948) at Jeju Island has long been an open secret among Korean intellectuals. Since 1987, media and academics have publicized several atrocities committed by the South Korean authorities during the Korean War. Korea’s civil society and democratic movement allowed the Commission, through its investigations into the South Korean government’s past wrongdoings, to throw an illuminating light on the dark chapters of colonialism, the Korean War, and the ultra-rightist consensus that held sway for half a century in Northeast Asia. Since the Associated Press’s report in 1999 on the No Gun Ri incident, other cases of victims of U.S bomb and strafing in the early days of the Korean War also came to be released.

Most of the petitions that the Commission received involved acts committed by South Korean authorities. Although most human rights abuses and massacres after 1948 were committed by South Korean authorities, some were implemented presumably with United States’ authorization and were carried out by Japanese-trained Korean soldiers and police. The legacy of Japanese colonialism and the US utilization of colonial machines and agents allowed for rampant human rights abuses and massacres in South Korea after 1945. The very presence of the United States military in South Korea contributed to the reinvigoration of fascist-minded Japanese collaborators, who undoubtedly exercised a negative influence on the building of democratic institutions. The oppressive colonial machinery left in political vacuum after World War II was revived by the U.S military government for the sake of containing communism. Serious misuse of governmental power in the form of massacres and state violence was tolerated in the name of safeguarding an anticommunist state. The South Korean government has to bear responsibility for these incidents, but their cause and character can only be understood in the context of Northeast Asian Cold War politics.

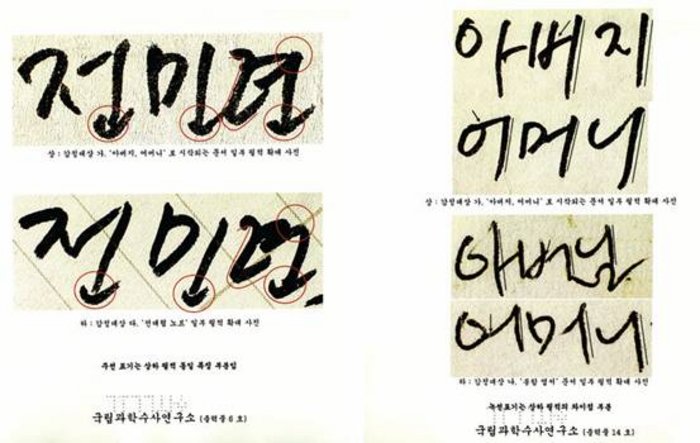

The Korean courts have re-examined and finally reversed the original decision on several controversial petitions on human rights abuses that the Commission has verified. In about ten cases, after retrials, courts have delivered findings of innocence, ordering the dropping of charges and compensation for the petitioners. In November 2007, for example, all charges were dropped against Kang Ki-hoon after 16 years, three of which he had spent in prison. He had been charged under the government of former President Roh Tae-woo in 1991 of forging the will and testament of his friend and fellow activist, Kim Ki-sul (who burned himself to death in May of that year in protest against the military government). The Roh Tae-woo government alleged that activists were encouraging people to kill themselves and were even prepared to ghost write their wills, and the case developed into a Korean version of the Dreyfus affair. It was only ended in 2007 with the release of the results of a fresh investigation by the National Institute of Scientific Investigation, or NISI, confirming that the will had indeed been written by Kim.

The TRCK ascertained from studies conducted by the National Institute of Scientific Investigation that the handwriting of Kim Ki-seo was clearly distinguishable from that of Kang Ki-hoon

Likewise, in January 2008, the case of Jo Yong-su, newspaper editor of the daily Minjok Ilbo, summarily executed in 1961 on charges of treason, was referred to the courts for retrial by the Commission and eventually, in January 2008, 47 years after his trial and execution, he was found innocent.

| Jo Yong-soo, president of the Minjok Ilbo daily, was summarily executed in 1961 by the military junta for treason and propaganda in favour of North Korea, just 30 hours after being sentenced (articles from Minguk Ilbo, 28 and 31 August 1961) |

And, in another similar case, in January 2007, the eight defendants in the “People’s Revolutionary Party” case, all executed in 1975 for attempting to form an illegal organization in cooperation with North Korea, were found at retrial to have been not guilty and the “People’s Revolutionary Party” itself an utter fabrication. Compensation was ordered to the families of the victims.

Most petitioners, especially the families of victims of the massacres, welcome the fact that a governmental organization has paid attention to their grievances for the first time. Korean citizens have been able to learn the newly verified truth. But the Commission has been less successful in terms of helping to establish restorative and preventive measures. Unbinding recommendations that the Commission gave to other concerned governmental organizations faced opposition and have not been sufficiently implemented. Faced with unfavourable political circumstances, the Commission has now found itself to be the weakest organization among existing Korean governmental organizations. Furthermore, conservative media almost completely ignore the work that Commission releases, choosing instead to reinforce past official versions of history. Some of the Commission’s findings, based on newly found testimonies and documents about United States bombing of South Korean civilians, demand a review of the Cold War system of control that seems to continue in Korea. The findings have the potential to be used to break the American-sponsored politics of denial that has been maintained for the last 60 years.

The work of the Commission would reveal the distorted history of Northeast Asia, no matter how sensitive the topic and no matter how few politicians pay attention. The truth that the Commission has tirelessly sought contains not only information on past politics in Korea and Korea’s interconnection with neighbouring big powers but also suggestions for Korea’s reunification and for peaceful relations in Northeast Asia. If the Commission fulfils its missions, the newly revealed historical facts must be fully publicized and translated for foreigners, and the recommendations must be accepted by the ROK government.

By restoring the honour of the victims and families, preventing reoccurrences of gross violations of human rights, and fostering reconciliation between the offenders and victims, the Commission’s work contributes to national solidarity and the growth of democracy. Its recommendations have included: official state apology, correction of the Family Registry, re-examination of evidence, memorial services, the correcting of historical records, archiving of historical files, legislation for relief of damages, restoration of damages, peace and human rights education, indemnity of damages, and treatment of after-effects. Many efforts have been made to resolve past conflicts and create a social environment for greater solidarity in the future.

Though the Commission remains a fragile organization within a relatively ‘weak country’ especially in the context of Northeast Asia, its very existence sets a precedent and example for other Asian countries. The investigations and finding of the Commission give moral and political lessons for East Asia, the United States and the rest of the world to learn from and to form a permanent path to peace and human rights.

Interactive video with testimony by a prison guard is here.

Notes

[1] For the Associated Press review of the evidence and its significance [with interactive video], Charles J. Hanley and Jae-Soon Chang, "Summer of Terror: At least 100,000 said executed by Korean ally of US in 1950," posted at Japan Focus, 23 July 2008, and Charles J. Hanley and Jae-Soon Chang, "Children 'Executed' in 1950 South Korean Killings: ROK and US responsibility,” Japan Focus,7 December, 2008.

Kim Dong-Choon, professor of sociology at Sung Kong Hoe University, is currently a standing commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Republic of Korea. He is author of many works in Korean, and in English, of The Unending Korean War: A Social History, Larkspur, Ca, Tamal Vista Publications, 2008.

The (English language) home page for the TRCK can be found here.

Kim Dong-choon wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal. Posted on February 21, 2009.

Gavan McCormack, emeritus professor at Australian National University, is a coordinator at Japan Focus. His most recent book is Client State: Japan in America’s Embrace.

Recommended citation: Gavan McCormack & Kim Dong-Choon, "Grappling with Cold War History: Korea’s Embattled Truth and Reconciliation Commission" The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 8-6-09, February 21, 2009.

- See more at: http://www.japanfocus.org/-kim-dong_choon/3056#sthash.XnCYdqj3.dpuf

No comments:

Post a Comment