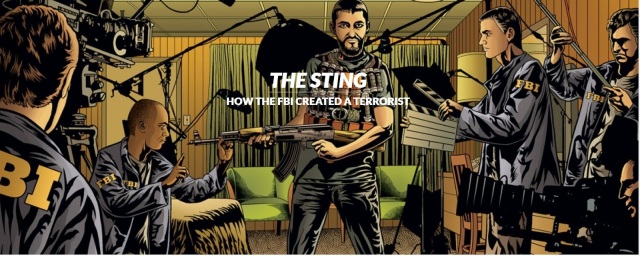

FBI có hẳn một chương trình và một đội ngũ “chuyên gia”, đi săn tìm

những cá nhân, Hồi giáo và không hồi giáo, có bệnh tâm thần, rồi khuyến

dụ, khuyến khích, cũng như hướng dẫn những nạn nhân này về vũ khí thuốc

nổ, rồi dàn cảnh QUAY PHIM – hoặc hướng dẫn những “kẻ khủng bố” này đến

một địa diểm để “hành sự khủng bố” đã có sẵn an ninh cảnh sát chờ đón

và… BẮT QUẢ TANG !!! Những thành quả “phá tan âm mưu khủng bố” này sau

đó được các đài báo chníh qui đăng tải thổi phồng kỹ lưỡng để làm nền

cho những ngân sách an ninh và các đạo luật an ninh xâm phạm dân quyền.

Nhưng mục tiêu quan trọng nhất vẫn là gây ly gián phân hóa quần chúng và khủng bố tinh thần quần chúng cho suy sụp, thụ động, và tuân phục.

Tờ Intercept của Glenn Greenwald tường trình một vụ điển hình.

FBI ĐÃ TẠO KHỦNG BỐ NHƯ THẾ NÀO?

IN THE VIDEO,

Sami Osmakac is tall and gaunt, with jutting cheekbones and a scraggly

beard. He sits cross-legged on the maroon carpet of the hotel room,

wearing white cotton socks and pants that rise up his legs to reveal his

thin, pale ankles. An AK-47 leans against the closet door behind him.

What appears to be a suicide vest is strapped to his body. In his right

hand is a pistol.

The recording goes on for about eight minutes. Osmakac says he’ll

avenge the deaths of Muslims in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan and

elsewhere. He refers to Americans as kuffar, an Arabic term for nonbelievers. “Eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth,” he says. “Woman for a woman, child for a child.”

IN THE VIDEO,

Sami Osmakac is tall and gaunt, with jutting cheekbones and a scraggly

beard. He sits cross-legged on the maroon carpet of the hotel room,

wearing white cotton socks and pants that rise up his legs to reveal his

thin, pale ankles. An AK-47 leans against the closet door behind him.

What appears to be a suicide vest is strapped to his body. In his right

hand is a pistol.

The recording goes on for about eight minutes. Osmakac says he’ll

avenge the deaths of Muslims in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan and

elsewhere. He refers to Americans as kuffar, an Arabic term for nonbelievers. “Eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth,” he says. “Woman for a woman, child for a child.”

In

July 2009, one of Sami’s older brothers had returned to Kosovo to get

married, and just before Sami was to fly to the Balkans with his

brother Avni for the wedding, he had a terrible dream. “An angel grabbed

me by the face and pushed me into the hellfire,” he would later tell a

psychologist. At the wedding, Avni took a photograph

of Sami; he’s clean-shaven and wearing a pressed white suit. He looks

happy. On the flight back from the wedding, during the final leg of

the journey to Tampa, the plane Sami and his brother were on hit

turbulence, losing altitude quickly. “I thought we were going to crash,”

Avni remembers. Sami looked horrified.

In

July 2009, one of Sami’s older brothers had returned to Kosovo to get

married, and just before Sami was to fly to the Balkans with his

brother Avni for the wedding, he had a terrible dream. “An angel grabbed

me by the face and pushed me into the hellfire,” he would later tell a

psychologist. At the wedding, Avni took a photograph

of Sami; he’s clean-shaven and wearing a pressed white suit. He looks

happy. On the flight back from the wedding, during the final leg of

the journey to Tampa, the plane Sami and his brother were on hit

turbulence, losing altitude quickly. “I thought we were going to crash,”

Avni remembers. Sami looked horrified.

That’s when something changed in him, according to his family and mental health experts hired

by both the government and the defense. Osmakac began to

isolate himself from his siblings and attend the mosque frequently. He

spoke of dreams about killing himself, and chastised family members for

being more concerned about this life than what comes after.

Meanwhile, Osmakac’s friendship intensified with the red-bearded

revert. Dennison, whose videos on YouTube are posted under the username “Chekdamize7,” frequently preached about

Islam and ranted about the corruption of nonbelievers.

Osmakac’s family believed that Dennison encouraged his extreme views,

often recruiting him to make videos. Among their efforts was a two-part series in which they argued combatively about religion with Christians they confronted on the sidewalk.

Nhưng mục tiêu quan trọng nhất vẫn là gây ly gián phân hóa quần chúng và khủng bố tinh thần quần chúng cho suy sụp, thụ động, và tuân phục.

Tờ Intercept của Glenn Greenwald tường trình một vụ điển hình.

FBI ĐÃ TẠO KHỦNG BỐ NHƯ THẾ NÀO?

IN THE VIDEO,

Sami Osmakac is tall and gaunt, with jutting cheekbones and a scraggly

beard. He sits cross-legged on the maroon carpet of the hotel room,

wearing white cotton socks and pants that rise up his legs to reveal his

thin, pale ankles. An AK-47 leans against the closet door behind him.

What appears to be a suicide vest is strapped to his body. In his right

hand is a pistol.

IN THE VIDEO,

Sami Osmakac is tall and gaunt, with jutting cheekbones and a scraggly

beard. He sits cross-legged on the maroon carpet of the hotel room,

wearing white cotton socks and pants that rise up his legs to reveal his

thin, pale ankles. An AK-47 leans against the closet door behind him.

What appears to be a suicide vest is strapped to his body. In his right

hand is a pistol.

“Recording,” says an unseen man behind the camera.

“This video is to all the Muslim youth

and to all the Muslims worldwide,” Osmakac says, looking straight into

the lens. “This is a call to the truth. It is the call to help and aid

in the party of Allah … and pay him back for every sister that has been

raped and every brother that has been tortured and raped.”

Osmakac in his “martyrdom video.” (YouTube)

Osmakac was 25 years old on January 7, 2012, when he filmed what the FBI and the U.S. Department of Justice would later call a “martyrdom video.” He was also broke and struggling with mental illness.

After recording this video in a rundown

Days Inn in Tampa, Florida, Osmakac prepared to deliver what he

thought was a car bomb to a popular Irish bar. According to the

government, Osmakac was a dangerous, lone-wolf terrorist who would have

bombed the Tampa bar, then headed to a local casino where he would

have taken hostages, before finally detonating his suicide vest once

police arrived.

But if Osmakac was a terrorist, he was

only one in his troubled mind and in the minds of ambitious federal

agents. The government could not provide any evidence that he had

connections to international terrorists. He didn’t have his own weapons.

He didn’t even have enough money to replace the dead battery in his

beat-up, green 1994 Honda Accord.

Osmakac was the target of an

elaborately orchestrated FBI sting that involved a paid informant, as

well as FBI agents and support staff working on the setup for more than

three months. The FBI provided all of the weapons seen in

Osmakac’s martyrdom video. The bureau also gave Osmakac the car bomb he

allegedly planned to detonate, and even money for a taxi so he could

get to where the FBI needed him to go. Osmakac was a deeply disturbed

young man, according to several of the psychiatrists and psychologists

who examined him before trial. He became a “terrorist” only after the

FBI provided the means, opportunity and final prodding necessary to

make him one.

Since the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the

FBI has arrested dozens of young men like Osmakac in controversial

counterterrorism stings. One recent case involved a rudderless

20-year-old in Cincinnati, Ohio, named Christopher Cornell, who

conspired with an FBI informant — seeking “favorable treatment” for his

own “criminal exposure” — in a harebrained plot to build pipe

bombs and attack Capitol Hill. And just last month, on February 25, the

FBI arrested and charged two Brooklyn men for plotting, with the aid of

a paid informant, to travel to Syria and join the Islamic State. The

likelihood that the men would have stepped foot in Syria of their own

accord seems low; only after they met the informant, who helped

with travel applications and other hurdles, did their planning take

shape.

Informant-led sting operations are central to the FBI’s counterterrorism program. Of 508 defendants prosecuted in federal terrorism-related cases

in the decade after 9/11, 243 were involved with an FBI informant,

while 158 were the targets of sting operations. Of those cases, an

informant or FBI undercover operative led 49 defendants in their

terrorism plots, similar to the way Osmakac was led in his.

In these cases, the FBI says paid informants and undercover agents are foiling attacks before they occur. But the evidence suggests — and a recent Human Rights Watch report on the subject

illustrates — that the FBI isn’t always nabbing would-be terrorists so

much as setting up mentally ill or economically desperate people to

commit crimes they could never have accomplished on their own.

At least in Osmakac’s case, FBI agents seem to agree

with that criticism, though they never intended for that admission to

become public. In the Osmakac sting, the undercover FBI agent went by

the pseudonym “Amir Jones.” He’s the guy behind the camera in Osmakac’s

martyrdom video. Amir, posing as a dealer who could provide weapons,

wore a hidden recording device throughout the sting.

The device picked up conversations, including,

apparently, back at the FBI’s Tampa Field Office, a gated compound

beneath the flight path of Tampa International Airport, among agents

and employees who assumed their words were private and protected. These

unintentional recordings offer an exclusive look inside an FBI

counterterrorism sting, and suggest that, even in the eyes of the FBI

agents involved, these sting targets aren’t always the threatening

figures they are made out to be.

ON JANUARY 7, 2012, after

the martyrdom video was recorded, Amir and others poked fun at Osmakac

and the little movie the FBI had helped him produce.

“When he was putting stuff on, he acted like he was nervous,” one of the speakers tells Amir. “He kept backing away …”

“Yeah,” Amir agrees.

“He looked nervous on the camera,” someone else adds.

“Yeah, he got excited. I think he got

excited when he saw the stuff,” Amir says, referring to the weapons that

were laid out on the hotel bed.

“Oh, yeah, you could tell,” yet another person chimes in. “He was all like, like a, like a six-year-old in a toy store.”

In other recorded conservations, Richard Worms, the FBI squad supervisor, describes Osmakac as a “retarded fool” who doesn’t have “a pot to piss in.” The agents talk

about the prosecutors’ eagerness for a “Hollywood ending” for their

sting. They refer to Osmakac’s targets as “wishy-washy,” and his terrorist ambitions as a “pipe-dream scenario.” The transcripts show FBI agents struggled to put $500 in Osmakac’s hands so he could make a down payment on the weapons — something the Justice Department insisted on to demonstrate Osmakac’s capacity for and commitment to terrorism.

“The money represents he’s willing to

do it, because if we can’t show him killing, we can show him giving

money,” FBI Special Agent Taylor Reed explains in one conversation.

These transcripts were never supposed to be revealed in their entirety. The

government argued that their release could harm the U.S. government by

revealing “law enforcement investigative strategy and methods.” U.S.

Magistrate Judge Anthony E. Porcelli not only sealed the transcripts,

but also placed them under a protective order.

The files, provided by a confidential source to The Intercept

in partnership with the Investigative Fund, provide a rare

behind-the-scenes account of an FBI counterterrorism sting, revealing

how federal agents leveraged their relationship with a paid informant

and plotted for months to turn the hapless Sami Osmakac into a

terrorist. Neither the FBI Tampa Field Office nor FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C. responded to requests from The Intercept for comment on the Osmakac case or the remarks made by FBI agents and employees about the sting.

SAMI OSMAKAC WAS 13 years old when he came to the United States with his family. Fleeing

violence in Kosovo in 1992, they had first traveled to Germany, where

they stayed until 2000, when they were granted entrance to the U.S. He was

the youngest of eight children, and he and his older brother Avni

struggled at first to adapt to a new land, a new language and a new

culture.

“We came to Tampa, and at first we

lived in this really bad neighborhood,” Avni recalls, wearing blue

jeans, spotless white Nikes and a white New York Yankees Starter cap.

“It was tough, but as we learned the language, things got easier. We

adapted.”

The Osmakac family opened a popular

bakery in St. Petersburg, across the bay from Tampa. They were Muslim,

but they rarely attended the mosque. They didn’t usually fast during

Ramadan, and Sami’s sisters did not cover their hair. Growing up, Sami

wasn’t particularly drawn to Islam either, according to his family. He

suffered the concerns many young men in the United States do, like

getting a job and saving up for a car.

In

July 2009, one of Sami’s older brothers had returned to Kosovo to get

married, and just before Sami was to fly to the Balkans with his

brother Avni for the wedding, he had a terrible dream. “An angel grabbed

me by the face and pushed me into the hellfire,” he would later tell a

psychologist. At the wedding, Avni took a photograph

of Sami; he’s clean-shaven and wearing a pressed white suit. He looks

happy. On the flight back from the wedding, during the final leg of

the journey to Tampa, the plane Sami and his brother were on hit

turbulence, losing altitude quickly. “I thought we were going to crash,”

Avni remembers. Sami looked horrified.

In

July 2009, one of Sami’s older brothers had returned to Kosovo to get

married, and just before Sami was to fly to the Balkans with his

brother Avni for the wedding, he had a terrible dream. “An angel grabbed

me by the face and pushed me into the hellfire,” he would later tell a

psychologist. At the wedding, Avni took a photograph

of Sami; he’s clean-shaven and wearing a pressed white suit. He looks

happy. On the flight back from the wedding, during the final leg of

the journey to Tampa, the plane Sami and his brother were on hit

turbulence, losing altitude quickly. “I thought we were going to crash,”

Avni remembers. Sami looked horrified.

Osmakac in 2009. (Photo courtesy of Osmakac family)

In December 2009, Osmakac met a

red-bearded Muslim named Russell Dennison at a local mosque. Dennison,

who was American-born, was described by Osmakac as a “revert.” Muslims

believe that all people are born with an understanding of the unity of

Allah, so when a non-Muslim embraces Islam, some Muslims refer to this

as reversion rather than conversion. Dennison went by the chosen name

Abdullah; he says in a YouTube video that after being introduced to Islam, his faith grew stronger during a prison term in Pennsylvania.

Osmakac’s dress changed after he met Dennison. Whereas he had once

saved his money to buy nice shoes and Starter caps, he suddenly began to

dress like Dennison, according to family members — cutting his pants

high at the ankle, buying cheap plastic sandals and sometimes wearing a keffiyeh on his head.

He refused to cut his beard, which he struggled to grow with any

thickness, and he wouldn’t wear deodorant that contained alcohol.

It wasn’t just his physical appearance

that was changing; by the beginning of 2010, his family also believed

he was deteriorating mentally. He’d become paranoid and delusional. His skin was pale. He was sleeping on the floor of his bedroom and complained about nightmares in which he burned in hell. He stopped working at the family bakery because they served pork products.

Near the end of the year, his family repeatedly asked him to see a

doctor. He rebuffed them, saying that the doctors would want to kill

him. (Osmakac later told a psychiatrist he in fact “was scared to go to a mental home.”)

Over the next year, Osmakac, who

was without steady employment, established a reputation as a firebrand

in the local Muslim community. He was kicked out of two mosques, and

lashed out at local Muslim leaders in a YouTube video, calling them kuffar and infidels. In

March 2011, Osmakac made his way to Turkey, in the hopes of traveling

by land to Saudi Arabia, according to his brother. He’d been told that

holy water from Mecca was a cure-all, Avni says — that if he drank it,

the nightmares would cease. But Osmakac never got much farther than

Istanbul, after encountering multiple transportation mishaps, and

getting turned away at the Syrian border by officials who refused to let

him cross without a visa. He quickly ran out

of money, lost his will and called home for help. His family in Tampa

helped purchase a plane ticket for him to return to Florida.

Osmakac would later tell several mental

health professionals that he was in fact more interested in traveling

to Afghanistan or Iraq to fight American troops, and perhaps even find a

bride there. “If I got to Afghanistan or Iraq, someone would marry me

to their daughter,” he mentioned to one psychologist. Osmakac got back in touch with Dennison in Florida, and would talk often of returning to a Muslim land so he could marry.

ON APRIL 16, 2011,

Osmakac was outside of a Lady Gaga concert in Tampa. Larry Keffer, a

Christian street preacher with short-cropped brown hair and a thick,

white beard, was outside the concert as well. Keffer was wearing a

fishing hat, a green camouflage shirt and blue pants.

“Sin is a slippery slope,” Keffer yelled through a megaphone to the Lady Gaga fans as someone else recorded the demonstration.

Most of the crowd ignored Keffer. A

few concertgoers taunted him. He taunted them back. A police officer

directing traffic refused to acknowledge the demonstration, while Keffer

ranted about Lady Gaga and the devil. Osmakac finally confronted

Keffer, pointing his finger in the preacher’s face.

“You infidel, I know the Bible better than you,” Osmakac told the preacher.

“What’s your message?” Keffer replied, talking into the megaphone.

“My message is, if y’all don’t accept Islam, y’all going to hell,” Osmakac said.

The men continued to provoke each other as people milled into the concert venue.

“Go have yourself a bacon sandwich,” Keffer told Osmakac.

“You infidel,” Osmakac said. “You infidel.”

As the argument escalated, Osmakac

charged one of Keffer’s fellow demonstrators and head-butted him,

bloodying the man’s mouth and breaking a dental cap. He then charged

Keffer. Each wrapped his arms around the other, turning and twisting,

until they broke free. The police officer managing traffic charged

Osmakac with battery, giving him notice to appear in court. Osmakac was

later arrested after failing to show up, Avni says, and his family had

to bail him out; in just a few months’ time, Osmakac’s red-bearded friend would lead him straight into an FBI trap.

SAMI OSMAKAC AND Russell

Dennison lived in Pinellas County, across the bay from Tampa.

In September 2011, Dennison told Osmakac he knew a guy who ran a Middle

Eastern market in Tampa. They should go see him, Dennison suggested. To

this day, Osmakac doesn’t know why Dennison suggested this, or why he

agreed to accompany him on the 45-minute drive to the store, called

Java Village, near the Busch Gardens theme park.

When they arrived, Dennison introduced

Osmakac to the owner, Abdul Raouf Dabus, a Palestinian. Dabus had

flyers in his store promoting democracy, and he and Osmakac argued about

the subject, with Osmakac contending that democracy and Islam were

incompatible.

“Democracy makes the forbidden legal

and the legal forbidden, and that’s greater infidelity,” Osmakac would

tell Dabus. “Whoever enforces it is an infidel, is a Satan. Hamas is

Satan. Muslim Brotherhood is Satan … If you don’t accept that God is

the only legislator, then you become a polytheist, and that’s why I’m

telling you.”

Osmakac didn’t know that Dabus would become an FBI informant. His work for the government has until now been secret.

According to the government’s version

of events, Osmakac asked Dabus if he had Al Qaeda flags, or black

banners. Osmakac disputes this, saying he never asked anyone for Al

Qaeda flags.

Whatever the truth, the sting had just begun.

A psychologist appointed by the court later diagnosed Osmakac with schizoaffective disorder.

“He asked me if he can work a couple of

hours, working and other stuff,” Dabus said in a phone interview from

Gaza, where he now lives. “But it wasn’t really like a job. So

basically, he was helping whenever he comes. And he got paid.” Dabus acknowledged he was paying Osmakac as the FBI was paying him.

In Tampa’s Muslim community, Dabus is well known. A former University of Mississippi math professor,

Dabus was an associate of Sami Al-Arian, the University of South

Florida professor who was indicted for allegedly providing material

support to the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, in a case prosecutors argued

proved successful intelligence-gathering under the Patriot Act. Dabus

had worked at the Islamic Academy of Florida, an elementary and

secondary private school for Muslims that Al-Arian had helped to found

in Temple Terrace, a suburb of Tampa.

Dabus was among the witnesses in the Al-Arian trial, and

his testimony was damaging to the government’s case. He testified that

he had known Al-Arian only to raise money for charitable purposes, not

for violence. During cross-examination, Dabus told the defense that he

feared that Al-Arian’s trial meant Palestinians in the United States

could no longer speak openly about the occupied territories. “There is

no longer any security for the dog that barks in this country,” Dabus

said.

He also questioned whether Al-Arian’s

indictment suggested Muslims had become a new target for the U.S.

government. “Our kids, will they have a future here?” he asked. “I don’t

know.”

While Al-Arian would continue to

battle federal prosecutors, living under house arrest in Virginia until

finally agreeing to deportation to Turkey this year, Dabus

remained in Tampa, active in the local religious and business

community. But he acquired a reputation during this time for running up

debts. From 2005 to 2012, he faced foreclosure actions on his home and

businesses, as well as breach-of-contract and small-claims cases.

In fact, when Dabus met Osmakac, he was in rough financial straits,

records show. In July 2011, the bank holding the mortgage on his

business’s building was granted approval to sell the property through

foreclosure; Dabus owed $779,447.

It’s unclear why Dabus became an FBI

informant, or for how long he worked with the government. He says he was

doing his civic duty in reporting Osmakac and the young man’s interest

in acquiring weapons, and had not previously worked with the FBI,

though an FBI affidavit in the Osmakac case described Dabus as having

“provided reliable information in the past.”

Money is a common motivator for FBI counterterrorism informants, who can

earn $100,000 or more on a single case. Dabus estimates the FBI paid

him $20,000 for his role in the Osmakac sting, though insists money did

not motivate him.

On November 30, 2011, after Osmakac had

begun working for Dabus, the two drove around the Tampa area together

as Dabus secretly recorded their conversation for the FBI. Osmakac

asked if Dabus could help him obtain guns and an explosive belt.

However, transcripts suggest he was also having trouble separating reality from fantasy.

“In the dream, I was shown that everywhere you go, everything you do,

hush your mouth,” Osmakac says. “Don’t say nothing. So, yes, the dream

is real. Allah showed me that dream for a reason. And he’s also

protected me for a reason.”

A psychologist appointed by the court later diagnosed Osmakac with schizoaffective disorder.

ABOUT THREE WEEKS after

this conversation, on instructions from the FBI, Dabus introduced

Osmakac to “Amir Jones,” an undercover agent. He might be able to help

Osmakac obtain weapons, Dabus told him.

“What are you looking for, so that I know if it’s something I can get you or not?” Amir asks Osmakac.

“I’m looking for, even if … one AK, at least,” Osmakac says.

“OK.”

“And maybe a couple of Uzi, ’cause they’re better to hide.”

“OK. OK.”

“If you can get the long extension like for the AK and the Uzi, the long magazines—”

“They’re called banana magazine,” Amir says. “OK.”

“And … couple of grenades, 10 grenades minimum, if you can,” Osmakac says.

“Now, and that’s it?” Amir asks.

“And a [explosive] belt.”

For all Osmakac’s talk, the FBI’s undercover videos

suggest he was less a hardened terrorist and more a comic book villain.

While driving around Tampa with Amir, a hidden FBI camera near the

dashboard, Osmakac described a plot to bomb simultaneously the several

large bridges that span Tampa Bay.

“That’s five bridges, man,” Osmakac

says. “All you need is five more people …. This would crush everything,

man. They would have no more food coming in. Nobody would have work.

These people would commit suicide!”

Amir Jones, behind the wheel of the car, offered a hearty laugh.

BACK AMONG FEDERAL law enforcement agents, according to the secret transcripts of their private conversations, there were plenty of reasons to joke at Osmakac’s expense. FBI

employees talked about how Osmakac didn’t have any money, how he

thought the U.S. spy satellites were watching him, and how he had no

concept of what weapons cost on the black market.

The source of their amusement was also

their primary source of concern. Osmakac was, in the FBI’s own words,

“a retarded fool” who didn’t have any capacity to plan and execute an

attack on his own. That was a challenge for the FBI.

“Once [the source] gives it to him, it’s his money, whether we orchestrated it or not.”

– Special Agent Taylor Reed

“Part of the problem is they want to

catch him in the act,” FBI Special Agent Steve Dixon says, referring to

federal prosecutors. “The attorneys do and stuff, but the problem is

you can’t show up at a nightclub with an AK-47, in the middle of a

nightclub, and pretend to start shooting people, or I mean people —”

“Right,” another speaker interrupts.

“— would get killed, just a stampede, just to get away from him,” Dixon finishes.

In constructing the sting, FBI agents

were in communication with prosecutors at the U.S. Attorney’s Office

for the Middle District of Florida, the transcripts show. The

prosecutors needed the FBI to show Osmakac giving Amir Jones money for

the weapons. Over several conversations, the FBI agents struggled to

create a situation that would allow the penniless Osmakac to hand cash

to the undercover agent.

“How do we come up with enough money for them to pay for everything?” asks FBI Special Agent Taylor Reed in one recording.

“Right now, we have money issues,” Amir admits in a separate conversation.

Their advantage was that Dabus, the

informant, had given Osmakac a job. If they could get Dabus to pay

Osmakac, and then make sure Osmakac used his paycheck to make a payment

toward the weapons, the agents could satisfy the Justice Department. “Once he gives it to him, it’s his money, whether we orchestrated it or not,” Reed says.

In conversations about this plan, FBI

agents refer to Dabus as the “source,” short for confidential human

source. “Jake” is FBI Special Agent Jacob Collins, who transcripts

indicate worked closely with Dabus.

“The source has to tell him, ‘Hey,

listen! You are gonna have to give [Amir] the three hundred bucks,’”

says Richard Worms, the squad supervisor. “And that’s something Jake has

the source tell him. ‘And I’ll take care of the rest … and here’s

three hundred of my money for you.’ Is that something you accept?”

“That’s a feasible scenario,” Amir Jones answers.

“That’s what you’re going to do,” Worms says. “That way, the source has to be coached what to do.”

In order to avoid being vulnerable to entrapment claims, the FBI agents didn’t want their money being used to purchase their

weapons in the sting. So they laundered the money through Dabus. In an

interview, Dabus implicitly confirmed that arrangement, describing the

$20,000 he estimates he received from the FBI as a mix of expenses and

compensation.

“It also shows good intent,” Worms

says of giving Osmakac the money, according to the transcripts. “He was

willing to cough up almost his entire paycheck to get this thing

going.”

“That does look really good,” concurs FBI Special Agent Taylor Reed.

AMIR AND OSMAKAC arranged to meet at a Days Inn in Tampa on January 7, 2012. The FBI had the room wired with two cameras,

a color one facing the headboard and a black-and-white one looking

over the bed and toward the closet door, in front of which Osmakac

would film his martyrdom video. Just as the FBI had orchestrated,

Osmakac provided the cash to Amir as a down payment on the weapons.

The hotel surveillance video starts at

8:38 p.m. Osmakac is kneeling down on the floor and praying. He then

stands and greets Amir, who has laid out the weapons on the bed. There

are six grenades, a fully automatic AK-47 with magazines, a handgun and

an explosive belt. Outside, a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device

is assembled in the bed of Amir’s truck. None of the guns or explosives was functional, but Osmakac didn’t know that.

“You know, they saying they like three

trillion in debt, they like 200 trillion in debt,” Osmakac had said,

describing their plot. “And after all this money they’re spending for Homeland Security and all this, this is gonna be crushing them.”

Amir shows Osmakac the weapons one by

one. He demonstrates how to reload the guns, and how to arm and throw

the grenades, as Osmakac had never received weapons training.

“This one’s fully automatic,” Amir says, as Osmakac holds the AK-47.

Osmakac then slips on the suicide

vest, as Amir showed him, and sits down in front of the closet, where

he’ll record his video. Amir is seated in a chair facing Osmakac,

holding the digital camera out in front of him.

The FBI was making a movie — all the agents needed was,

in their words, a “Hollywood ending.” Osmakac would give them that

final scene.

Osmakac had settled on an Irish bar,

MacDinton’s, as his target. The supposed plan, which Osmakac dreamed up

with Amir, was for Osmakac to detonate the bomb outside the bar, and

then unleash a second attack at the Seminole Hard Rock Hotel &

Casino in Tampa, before finally detonating his explosive vest once the

cops surrounded him.

But that didn’t happen. Instead, FBI agents arrested him in the hotel parking lot. He was charged with attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction — a weapon the FBI had assembled just for him.

After the arrest, according to the sealed transcripts, the FBI agents intended to celebrate their efforts over beers.

“The case agent usually buys,” one of

the FBI employees is recorded as saying. Another adds: “That’s true —

the case agent usually pops for everybody.”

HOW OSMAKAC CAME

to the attention of law enforcement in the first place is still

unclear. In a December 2012 Senate floor speech, Dianne Feinstein,

chairwoman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, cited Osmakac’s case as

one of nine that demonstrated the effectiveness of surveillance under

the FISA Amendments Act. Senate legal counsel later walked back

those comments, saying they were misconstrued. Osmakac is among

terrorism defendants who were subjected to some sort of FISA

surveillance, according to court records, but whether he was under

individual surveillance or identified through bulk collection is

unknown. Discovery material referenced in a defense motion included a

surveillance log coversheet with the description, “CT-GLOBAL EXTREMIST

INSPIRED.”

If he first came onto the FBI’s radar as a result of

eavesdropping, then it’s plausible that as part of the sting, the FBI

manufactured another explanation for his targeting. This is a

long-running, if controversial process known as “parallel construction,”

which has also been used by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration

when drug offenders are identified through bulk collection and then

prosecuted for drug crimes.

In court records, the FBI maintained

that Osmakac came to agents’ attention through Dabus. The informant

reached out to the FBI after meeting Osmakac, and soon offered him a job

at Java Village.

At trial starting in May 2014, Osmakac’s lawyer, George Tragos, argued that the Kosovar-American was a young man suffering from mental illness, who had been entrapped by government agents.

A difficult defense to raise,

entrapment requires not only that the government create the

circumstances under which a crime may be committed, but also that the

defendant not be “predisposed” toward the crime’s execution. “This

entire case is like a Hollywood script,” Tragos told the jury, pointing

out that the central piece of evidence was that Osmakac used

government money to buy government weapons.

A psychologist retained by the defense,

Valerie McClain, testified that Osmakac’s psychotic episodes, along

with other mental health issues, made him especially easy for the

government to manipulate. “When I talked to him most recently, he was

still delusional,” McClain testified. “He still believed he could

become a martyr.” Six mental health

professionals examined Osmakac before his trial. Two hired by the

defense and two appointed by the court diagnosed Osmakac with psychotic

disorder or schizoaffective disorder. The pair hired by the

prosecution said Osmakac suffered from milder mental problems,

including depression and difficulty adapting to U.S. culture.

Tragos wasn’t able to tell the jury

that FBI agents might have agreed with McClain’s assessment of Osmakac.

The transcripts of the accidentally recorded conversations among FBI

agents weren’t allowed into evidence, but after the trial,

District Judge Mary S. Scriven did agree to unseal a number of them,

which were heavily redacted by the government before being entered into

the court file.

Prosecutors relied on the undercover

FBI recordings and Osmakac’s own words to convict him. They played for

the jury Osmakac’s so-called martyrdom video. They showed footage of

Amir slipping over Osmakac’s shoulder the strap for the AK-47. They

filled the courtroom with exchange after exchange of Osmakac’s hateful

and violent rhetoric. Prosecutors played up Osmakac’s most ridiculous

remarks, including his desire to bomb simultaneously the bridges that

cross Tampa Bay. “The most powerful thing you can see are the

defendant’s own words. His intent was to commit a violent act in

America,” prosecutor Sara Sweeney told the jury.

Following a six-hour deliberation,

jurors convicted Osmakac of possessing an unregistered AK-47 and

attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction. In November 2014, he

was sentenced to 40 years in federal prison.

“I wanted to go and study the religion … hoping that Allah is gonna cure me one day from the evil inside that I used to believe. But the doctors are saying it’s not evil — it’s mental illness.”

– Sami Osmakac

Entrapment has been argued in at least 12 trials

following counterterrorism stings, and the defense has never been

successful. Neither Abdul Raouf Dabus nor Russell Dennison testified in

or provided depositions for Osmakac’s trial.

The government couldn’t produce Dabus,

the FBI’s informant, because he had traveled to Gaza and Tel Aviv,

where he says he was receiving treatment for cancer. He says his

involvement with the FBI was limited to the Osmakac case — to

reporting a suspicious man who was asking about Al Qaeda flags. Dabus

disputes the FBI’s claim in court records that he was known to provide

reliable information in the past.

“I did my job with them. I went away,

and it is over,” Dabus says. “But I do not regret, and I would never

regret to call again.”

Before Dabus left the country, the bank was granted approval to sell his Tampa home through foreclosure. His family owed $302,669, or about $50,000 more than the house was worth. Java Village is now shuttered. The

signs are still on the outside of the building. Inside, the shelves

are knocked over. Canned and dry goods litter the floor. Two dogs now

guard the property.

Dennison, the red-bearded man who introduced Osmakac to Dabus, remains a mystery. He

left the area shortly after Osmakac’s arrest, and emails he sent in

late 2012 to a mutual friend he shared with Osmakac suggest he was

fighting in Syria.

Osmakac’s family suspects much of

Dennison’s story is a lie, and that he was, and likely still is, working

with government agents. How else could Dennison have so conveniently

delivered Osmakac to Dabus?

Confidential FBI reports on Dennison, copies of which were provided to The Intercept,

do not address whether he’s been linked to a government agency. But

the reports suggest the red-bearded man had a peculiar knack for

becoming friendly with targets of FBI stings. After Osmakac’s arrest,

FBI Special Agents Jacob Collins and Steve Dixon interviewed Dennison

at Tampa International Airport, according to one report.

Dennison was headed to Detroit, and from there, he said he hoped to go

to Jordan to teach English. Dennison described how he was in contact

with Abu Khalid Abdul-Latif, whose real name is Joseph Anthony Davis, a

36-year-old Seattle man who, like Osmakac, was troubled and financially

struggling, lured by a paid informant into an FBI counterterrorism

sting in June 2011. Abdul-Latif is serving 18 years for his crime.

Osmakac is now in USP Allenwood, a high-security prison north of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

“I was manipulated by [the FBI],”

Osmakac says in a phone call from prison. He says he only wanted to move

to a Muslim country, where he hoped to find a wife. Instead, he says,

Dabus and the FBI exploited his mental problems and pushed him in

different direction.

“I wanted to go and study the religion

and get married, have children, just have nothing to do with this

Western world,” Osmakac says. “I wanted to study Arabic and the religion

in depth, hoping that Allah is gonna cure me one day from the evil

inside that I used to believe. But the doctors are saying it’s not evil —

it’s mental illness.”

Osmakac’s family is trying to raise money for an appeal.

“If my brother was truly part of a

plot to kill people, I’d be the first one in line to condemn him,”

Osmakac’s brother Avni says. “But my brother was mentally ill. We were

trying to get him help. The FBI got to him first.”

This story was reported in partnership with the Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute.

No comments:

Post a Comment